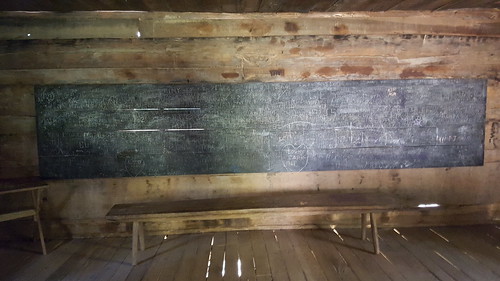

The trail head is located just north of MetCalf Bottoms picnic area. It starts off at an old school house where classes were from taught from 1882 till 1935.

The trail follows along side a small branch called Little Brier Branch as it gradually climbs out of the hollow. At about six-tenths of a mile, you will reach a foot bridge.

At about 1.1 miles you will reach the side trail that leads over to the Walker’s Sister Place a short distance away.

Old Spring House.

This was again a very pleasurable hike and it’s good to be able to learn about some of the history of the Great Smoky Mountains area. Temperatures were perfect and nothing but sun in the sky. For anyone interested in the history of the Walker Sister’s Place, I’ve quoted some information below, thanks for reading folks!

Little Green Brier achieved a degree of national fame as a result of the Walker Sisters. The five spinster sisters who lived here refused to sell their 123-acre farm to the national park, and were able to maintain their traditional mountain life into the 1960’s.

John Walker, a Union Army veteran, and his wife, Margaret, moved onto the homestead in 1870. Over the years, as his family grew to eleven children, John expanded the cabin and made several improvements to the farm. At one point the homestead consisted of several outbuildings, including a barn, blacksmith shop, applehouse, springhouse, smokehouse, pig pen, corn crib and a small tub mill. Today, only the cabin, springhouse and corn crib survive at the site.

In 1909 Walker deeded the land to his youngest son, Giles, and five of his daughters; Margaret (1870-1962), Martha (1877-1951), Nancy (1880-1931), Louisa (1882-1964) and Hettie (1889-1947). By this time the other children were already married and had moved away. After John died in 1921 the farm was passed to the five daughters (later in that same year Giles would deed his share of the land over to his sisters).

While the surrounding mountain communities slowly began to modernize after World War I, the Walker Sisters continued to pursue their traditional way of life, which emphasized independence and self-reliance. The five sisters would continue to raise sheep, grow crops, plow their own fields and make their own clothes from the wool and cotton they raised.

Change, however, would be forced upon the Walker Sisters. In the 1930s the Great Smoky Mountains Park Commission, responsible for purchasing property for the new national park, tried to persuade the sisters to sell their farm. Realizing that the park was wading into a public relations minefield, GSMNP Superintendent Ross Eakin sent a memorandum to the Director of the National Park Service on Nov. 18, 1939, stating; “These old women are ‘rooted to the soil.’ We have always understood they were to be permitted to spend the rest of their lives on their property. . . . If they were ejected from the park we should be subject to severe criticism, and in my opinion, justly so.”

Finally, in late 1940, faced with a condemnation suit, the Walker Sisters accepted $4,750 for their land, provided they were “allowed to reserve a life estate and the use of the land for and during the life of the five sisters.” On January 22, 1941, ownership of the Walker Sisters’ land finally passed to the national park. A local legend claims that President Franklin Roosevelt paid a visit to the sisters and convinced them to sell the farm to the new park. Although Roosevelt was in the area to dedicate the national park in 1940, there’s no evidence of him having visited the sisters.

The National Park Service assumed control of the land when Louisa, the last of the Walker Sisters, died in 1964. The National Park Service restored the cabin in 1976, and in that same year, all three surviving structures on the site were placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Leave a comment